On November 29, the landmark Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) celebrated its 50th birthday. I know I am a week late writing this post, but remember that I have a day job, a wife, and five kids, ages 10-2. As the wisecrack goes, “I’m workin, here!” 🙂

Originally called the “Education for All Handicapped Children Act,” it was signed into law by President Gerald Ford on November 29, 1975 in order to establish the right of students with disabilities to receive a “Free and Appropriate Public Education” (FAPE) in the least restrictive environment (LRE), and in part, to help alleviate the litigation stemming from the enactment of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. For those who do not know, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 prohibited any entity or program receiving federal funds–including public schools–from discriminating on the basis of disability.

In 1971, only 20% of students with disabilities were served by the public schools, and many states had laws barring students with intellectual or developmental disabilities from the public schools. It was c ommon for parents of children with disabilities to be told by medical personnel to leave their infant in the hospital to die (and be refused medical care), or send them off to a state institution like Willowbrook State School-a squalid institution for people with disabilities in Staten Island, New York dubbed a “snake pit” in 1965 by U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy due to its filthy, overcrowded conditions and unethical hepatitis “experiments” on children, and then made infamous in a 1972 Geraldo Rivera exposé.

In fact, Judy Heumann, born in 1947 and considered the Mother of the Disability Rights movement, contracted polio at 18 months old and spent most of her life in a wheelchair. The New York City Public Schools forbade her from attending school, and she received in-home instruction twice a week for about an hour. She was allowed to attend high school in 1961 after her parents and others fought to reverse the policy prohibiting students with physical disabilities from attending school with their peers.

After graduating from college and obtaining a Master’s degree, Judy was denied a teaching license by the City of New York because the District claimed that she could not safely lead her students to safety in the event of a fire. In 1975, she sued–and won–teaching elementary school in the New York City Public Schools for three years. Noting the irony of having had a President (Franklin D. Roosevelt) who served three terms in the White House and got elected to a fourth some three decades prior–all while in a wheelchair–one New York paper ran a headline, “You Can Be President, Not Teacher, with Polio.”

Later, Heumann would go on to lead the occupation of a Federal Building in San Francisco to demand that Secretary James Califano, Jimmy Carter’s Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, promulgate the federal regulations required by Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. The regulations were finally promulgated in 1977, and a movement was born. Heumann would go on to spearhead the independent living movement and include disability in U.S. foreign policy through appointments at the World Bank and the State Department. Judy never abandoned her motto, “Lead on!” until her death in 2023.

“Crip Camp,” a Netflix documentary about a summer camp for kids with disabilities that Judy attended, is highly recommended for those seeking to learn more about the disability rights movement.

In 1990, EHA was reauthorized by Congress, which renamed the law the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), a name it has been known by ever since. In 2004, President George W. Bush signed into law the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act, reauthorizing IDEA.

Yours truly was born in 1986 and diagnosed with spastic cerebral palsy shortly after birth, after experiencing a traumatic birth. I experienced a neurological insult as a result of meconium aspiration and persistent fetal circulation. In layman’s terms, during birth, I began aspirating. Meconium clogged my lungs and caused oxygen deprivation and brain damage, and hence the CP.

I benefited from Part C of IDEA, which provides Early Intervention services to infants and toddlers with disabilities or developmental delays, including physical, occupational, and speech therapy. In the 1989-1990 school year, I participated in a pilot program that placed students with disabilities in a mainstream classroom at Peter Noyes Elementary School in Sudbury, MA, where my family resided. There were other students with disabilities in the class from the surrounding towns, including Framingham and Marlborough. Somewhere in my house or in my parents’ attic is a handmade book with pictures of me in this program – including one in which I was playing dress-up with a fellow student and wearing a kimono, wooden shoes, and a sombrero simultaneously. I was VERY multicultural from a young age.

In 1990, my family moved from Massachusetts to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where I grew up. However, it was first suggested by the school district to my mother that I be placed in a separate classroom with other disabled kids, instead of the regular classroom, even though I had been mainstreamed in Massachusetts.

“This isn’t Massachusetts,” my mother was told, even though Chapel Hill is home to the University of North Carolina, and Duke University (and its world-class hospital) is 7 miles down the road in Durham. As I was not quite ready for Kindergarten, I was allowed to enroll in Head Start and then entered Kindergarten in 1992.

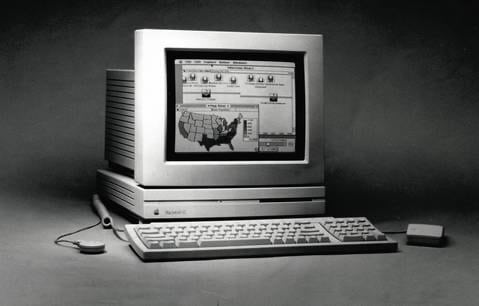

I attended Pre-K through 12th grade in the Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools, taking Honors and AP classes in high school. Starting in first grade, I had a Macintosh LC desktop computer to help me do my written work, as my CP affects my fine motor skills and makes it difficult for me to write legibly by hand. Peers would always want to sit near my desk so they could be first in line to ford the river, or die of tuberculosis or dysentery when we were allowed to play Oregon Trail on the big, huge floppy disks.

As I got older and technology evolved, I had an Alphasmart–Apple’s word processing keyboard from the late 1990s, and eventually a Compaq laptop that weighed about 15 pounds. When I got a sleek, 2-lb laptop in high school, I felt totally futuristic.

Starting in middle school, I had one set of textbooks at school and one at home so that I wasn’t carrying a 60lb backpack. I also had scribes in math class and notetakers in other classes, accommodations that followed me through college.

Throughout my time in public school, I received physical, occupational, and speech therapy on a weekly basis, as required by my Individualized Education Plan (IEP).

My K-12 experience was marked by some wonderful teachers and therapists who never let me use my disability to weasel my way out of responsibility or submit subpar work when they knew what I was capable of. My mom, Patti, was a fierce advocate for me in IEP meetings, ensuring I got the assistive technology and services I needed to succeed at school-even when the District dragged its feet. I am certain there were people at CHCCS central offices who got tired of hearing from my mother, but she did what she had to in order to ensure my academic success.

Mom always asked around to see which teachers were known for being good teachers to students with disabilities and always worked, especially in high school, with my guidance counselor to select my teachers. The reality is that some teachers don’t want to be bothered with IEPs and accommodations, so it’s best to avoid those situations if it’s possible to do so.

And yes, there was bullying, especially in elementary school. I was made fun of on the playground and the school bus because of my disability. Until I was about 8 or 9, I drooled a lot. I had three out of four of my saliva glands surgically removed at Duke over the summer, which eliminated the drool issue.

As I reflect on 50 years of IDEA, I can’t help but wonder how my life would have been different had I been born in 1956 instead of 1986. There is, of course, the small matter of whether or not I would have even survived, given that only 2% of neonates born in my condition survived in 1986, but putting that aside, what would my educational experience have looked like? A squalid institution? I shudder to think.

I graduated from Chapel Hill High School in 2005, and attended the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. for my freshman and sophomore years of college before transferring to UNC as a junior (yay, in-state tuition!)

My experience in the public school system and the protections afforded to me as a disabled student by IDEA no doubt laid the trajectory for success throughout my childhood and into adulthood. The wonderful teachers I had that formed me into the person I am today-Mrs. Sickink, Ms. O’Neal, Ms. Gronback, Mr. Link, Ms. Works, Ms. Maples, Mrs. Kalleberg, Mrs. Sharp, Mrs. Maiani, Mr. Ruffle, Mr. Melega, Mr. Greenberg, Mr. Blackwell, Mrs. Jones, Mr. Williams, Ms. McClelland, and Ms. Lawson are folks I still remember all these years later. Not only were they good to me and integral to my success–they also put up with more than their fair share of nonsense from me!

As I look at my life and all that I see in it – my wife and kids, my career – I thank God for all the wonderful educators who were placed in my path, and most especially, for IDEA, which made it all possible.

Leave a comment